|

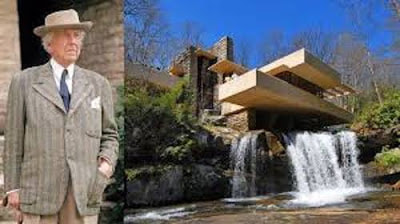

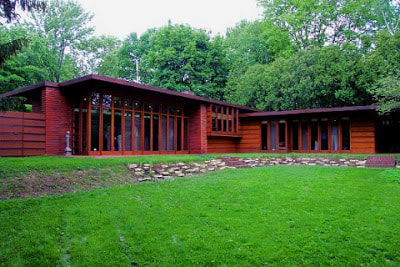

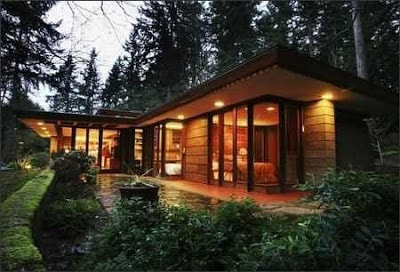

Frank Lloyd Wright continues to impact our lives every day.  FLW and Fallingwater “I would rather solve the small-house problem than build anything else I can think of.” In 1991, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) officially declared Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) “the greatest American architect of all time.” International academia considers him one of the three or four greatest modern architects of all time in the world (but possibly also one of the biggest divas amongst architects, and certainly a difficult one). Wright’s name conjures images of such iconic FLW buildings as the Guggenheim Museum, the swirling concrete sculpture in New York City; Taliesin West, his iconic school of architecture in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert; and Fallingwater, the masterpiece he built into the rocky side of a mountain and above a waterfall in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. These are only three out of 500-plus projects he completed over his 70-year career. Yet to this visionary genius from Wisconsin, solving the American suburban “small-house problem” for “the common people” was a persistent mission. And the solutions he found forever changed the paradigm of residential design. If you’re sitting in a modern or “contemporary” house right now, you’re enjoying Wright’s genius right now without even knowing it. _______________________________________ “I believe in God, only I spell it N-a-t-u-r-e.” _______________________________________ Frank Lloyd Wright’s devotion to “organic architecture,” as he called his guiding ethos, influenced everything he designed. So he looked to forms found in nature for inspiration. The design for the Guggenheim, for example, was reportedly based on a shell. Fallingwater – voted the “best all-time work of American architecture” by the AIA – is, in essence, an outcropping on the mountainside. Wright’s work was never ostentatious – not even his largest, most expensive houses. He believed in clean lines and simplicity and despised the restraints and unnecessary ornamentation of architectural styles that preceded him, especially tthe ornate fussiness of the Victorian era. FLW's 1920 Frederick Robie House, the epitome of his Prairie style. To Wright, American homes needed to be more open, airy, and livable for everyday citizens. He saw the need for fewer, larger rooms conducive to family life, with an abundance of natural light and easy access to the outdoors, both physically and through constant views. His philosophy was manifest in all of his work, including the Prairie Style houses (his term) he designed for the mid-western U.S. (1893 to early 1900s) and later in the small, one-story “Usonian” houses, as he named them, that he conceived during the Great Depression. The 1936 Jacobs "Usonian" House Of the latter, Wright knew his clients would emerge from the Depression destined to lead simpler lives without household help. They were going to need affordable, sensible, aesthetically pleasing homes. Among other considerations, this would require consolidated functionality. ______________________________________ “The architect must be a prophet…a prophet in the true sense of the term…If he can’t see at least ten years ahead, don’t call him an architect.” ______________________________________ So – you’re sitting in your modern or contemporary house right now, and you’re wondering where the great man’s influence still lurks. If you’re an architect, you already know. If not, prepare to be amazed: FLW created deep, cantilevered roof overhangs to protect all of his windows. (1) The hallmark of Wright’s groundbreaking Prairie Style was its horizontal emphasis – “a companion to the horizon,” he said. One way in which he expressed that emphasis was with his use of flat or hipped roofs with deep, cantilevered overhangs. (2) A pioneer in structural glass: The roof overhangs were necessary to shade all those wonderful horizontal bands of windows and floor-to-ceiling glass doors that allowed natural light and panoramic views of nature to fill the interior.  FLW stunned the world with his concept for open floor plans, like the one above. (3) Wright introduced the concept of open floor plans, a fresh and rather startling concept then, but de rigueur in all modern homes after it became popular post-WWII. The concept was not only beautiful and comfortable, but it also consolidated functionality rather than dividing the home’s function into a series of separate, confining-areas. As a result, Wright achieved the “fewer, larger rooms” he advocated for modern American living, as well as the open airiness we still love about modern houses today. (4) Wright was both an artist and a pragmatist. As the latter, he knew that without domestic help, the post-Depression wife/mother (as was the norm then) would need to keep an eye on her children while performing her work in the kitchen. The open floor plan aided that. It also banished the claustrophobic kitchen that kept her away from family and friends. He installed skylights in the kitchen ceiling to provide natural light since the “workroom of the house,” as Wright called it, was often in the windowless core of the house. (5) Other kitchen innovations we take for granted that sprang from FLW’s genius:

(6) To avoid costly, time-consuming plasterwork, Wright specified more efficient, less expensive pre-finished plywood for his interior walls – arguably the precursor to drywall. (7) Construction technique and materials: Wright was the first architect to use new building materials – concrete and steel – in domestic architecture, including cost-efficient and durable concrete block construction. He hid the humble blocks behind veneers of more attractive materials, such as wood, stone, and brick (depending on the place in which the house was built). (8) By embracing those construction materials previously relegated to commercial buildings, he was able to create L-shaped footprints for his houses. The “L” enclosed and overlooked a back yard/courtyard/private garden for the suburban homeowner – another way to blur the boundary between indoors and outdoors. (9) Functional innovation: The L-shape also let him separate the bedrooms from the more “public” areas (living/dining/kitchen) in a one-level house. He believed this separation was vital for harmonious family life. Wright invented the carport. On this FLW house, it's carport-as-sculpture. (Photo James Michael Kruger)

(10) He took advantage of other technical advancements to reduce costs for his clients. For example, furnaces had become smaller and cleaner. So he eliminated basements, opting instead for less expensive concrete slab foundations. He ran pipes through the slab for radiant heating. Many well-kept mid-century modern houses still feature their original under-the-floor heating. (11) When automobile design and materials made them less vulnerable to the elements, Wright also reduced construction costs by replacing garages with “carports” – a term he coined. * * * These are only a few elements of modern and contemporary houses that we take for granted today. So when you have a few minutes, look around your own house. Chances are you’ll find several reasons to thank Frank.

0 Comments

|

AuthorTobias Kaiser works as an independent real estate broker and consultant in Florida since 1990. Always putting his clients' interest first, he specialises in modern Florida homes and architecture, as well as net leased investments. Archives

April 2024

|

- Home

- Modern Homes for sale

- Selling a Home

- Inquiries

- Why Tobias Kaiser?

- Contact

- "Modernist Angle" Blog

- Services we offer

- South Florida City Profiles

- Intro to Modernism

- Modern Styles explained

- Elements of Modern Architecture

- Preservation

- Real Estate FAQ

- Deutsche Seite >

- Net-Leased Investments >

- About Tobias Kaiser

|

|

KAISER ASSOC, INC • LIC FLORIDA REAL ESTATE BROKERS & CONSULTANTS

dba MODERN FLORIDA HOMES • 370 CAMINO GARDENS BLVD • BOCA RATON, FLORIDA 33432, USA TOBIAS KAISER, MSc, CIPS • REALTOR/BROKER • MODERN ARCHITECTURE SPECIALIST MEMBER NAR, RCA, DOCOMOMO, NCMH • EMAIL • (+1) 954 834 3088 ZERO DISCRIMINATION: Kaiser Assoc. and its agents will not discriminate against any person because of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin in the sale or rental of housing or lots, in advertising the same, in the financing of housing in the provision of real estate brokerage services, in the appraisal of housing, or engage in blockbusting. Kaiser Assoc. strictly adheres to the National Association of Realtors© Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice in accordance with Federal Fair Housing Laws. "SILENCE IS CONSENT": As a multi-cultural office neither do we silently consent to nor do we tolerate any type of discrimination, racism or prejudice. We strive to listen and learn what needs to be done to implement permanent change. Site design + contents ©Tobias Kaiser 2024. PUBLICATION, USE OR REPRODUCTION incl. parts ONLY WITH WRITTEN PERMISSION. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed